Sunday, July 17, 2016

We woke up early to board the LC-130 Hercules for our 2 ½ hour flight to camp EGRIP. The Hercules is equipped with skis, which enable the US National Guard to land on Greenland’s ice sheet.

There were 27 of us on this flight including Bill Nye (The Science Guy) with a documentary film crew of four. Also present was Jim White (Director of the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado), and a small Chinese Delegation that would observe the EGRIP station for two hours before returning to Kangerlussuaq.

Cockpit inside LC-130 Hercules

Our group inside the Hercules

We arrived at EGRIP at 12:30 to find that we needed our moon boots and cold weather gear since the temperature was 11 degrees F.

The East Greenland Ice Core Project (EGRIP) is located over the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream (NEGIS). The NEGIS flows at a rate of 60 meters per year and empties into the Nordic Sea in 3 different locations. There are several streams under Greenland’s ice sheet. Each one flows at a different rate and contributes to the rise in sea level.

We were greeted Dorthe Dahl-Jensen, Chair of the EGRIP project. Dorthe is a paleoclimatology professor and researcher at Centre for Ice and Climate at the University of Copenhagen. Her team reconstructs climate records from ice cores and boreholes that extend back as far as 100,000 years.

While drinking coffee and homemade cinnamon buns in the “Dome”, Dorthe gave us a briefing about EGRIP and the importance of gathering data from the ice cores that will be drilled there.

After dropping our duffels into our respective tents, we watched the Chinese delegation return to Kangerlussuaq on the LC-130.

The camp at EGRIP consists of a large black dome, seven red sleeping tents, several maintenance tents and the drill pit.

My living quarters.

All our communal activities occur in the dome.

There is a kitchen, dining, lounge, one shower, two sinks, two toilets, plus a washer and dryer for the whole camp.

The main attraction is the drill pit where most activities occur. This facility consists of several rooms that are constructed by placing large balloons in hand-dug underground pits. Two meters of snow are then blown with a piston bully over the openings, creating a roof.

The longest room houses the drill, tables to place the ice cores, and equipment that will analyze the cores. This room houses a 14-meter deep pit where the drill will be lowered and drilled into Greenland’s ice sheet.

Another room will act as a storage facility for the cores. Each one will be placed on individual troughs that have been labeled according to the depth of the core. EGRIP will drill down to the bedrock, 2600 meters below the surface of the ice. The cores that are between 600-1200 meters deep will be stored for one year. The pressure on the air bubbles in the ice at this depth makes the ice quite brittle, and these cores will need to rest before they can be analyzed.

After a delicious dinner prepared by Josephine, the amazing chef at EGRIP, we watched the movie Camp Century.

During the 1950’s Cold War, the United States wanted to increase its military capabilities against the Soviet Union in case of nuclear warfare. Military operations in the Arctic and Subarctic would give the United States the shortest route to strike targets in the Soviet Union. Project Iceworm was the code name for the US Army program titled “Camp Century”.

The location of Camp Century in Greenland.

Credit: William Colgan

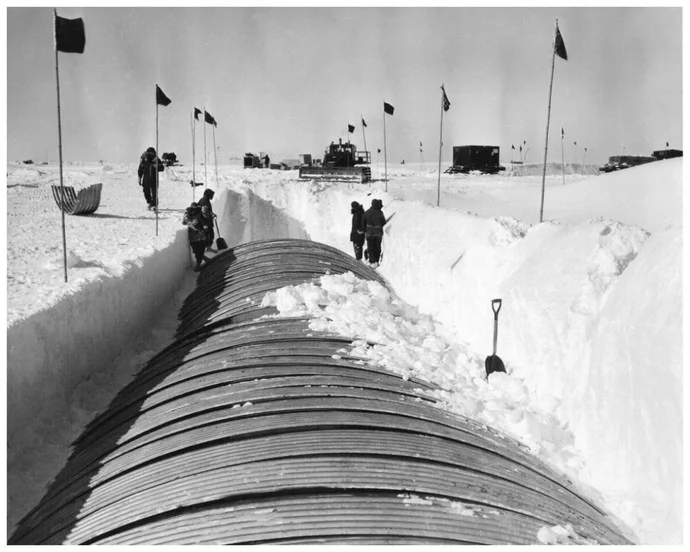

The proposal was for the United States to build a network of nuclear missile launch sites under the Greenland ice sheet undetected by the Soviet Union. The Danish Government was informed that the purpose of Camp Century was to test various construction techniques under Arctic conditions. Trenches were cut and covered with arched roofs and prefabricated buildings were placed inside these trenches, including a hospital, shop, theater and a church. Electricity was supplied by the world’s first portable nuclear reactor, and water was supplied by melting glaciers.

Geologists took ice core samples within three years of excavation. These samples demonstrated that the glacial ice sheet was moving much faster than was anticipated, which would result in a collapse of the tunnels. Camp Century would never become a nuclear missile base but the information on Arctic construction techniques and Arctic living was invaluable to climatologists in pursuing ice core drilling.

The group was both excited and exhausted from this stimulating day.

Before crawling into my mummy sleeping bag, I took one last photo.